28 September is UNESCO’s International Day for Universal Access to Information, formerly known as Right to Know Day. The slogan of this year’s celebration is ‘Leaving No One behind’. What is the status of citizen’s access to information (ATI) legislation in Africa?

Determining how legislation can contribute to upholding transparency, accountability, and good governance through ensuring citizen’s rights to access to information is a cornerstone of the democratic process and a key determiner of development. ATI laws enshrine this potential, providing a legal instrument for citizens to request and access government information, documents and records from government bodies about official rules and activities.

African ATI laws

Legal frameworks to regulate information flow and availability are increasingly more common. Across the globe, there has been a recent surge in the adoption of ATI laws. Today, over 120 countries have adopted such laws, covering most of Europe, America and Asia.

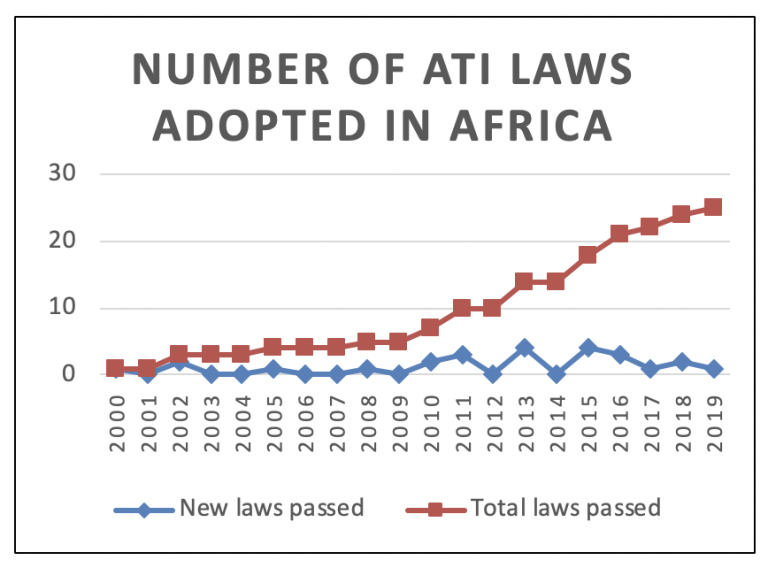

When the Ghanaian parliament adopted the long-awaited Right to Information (RTI) Bill on 26 March this year, the total of African countries with an explicit law on citizen’s right to access information was brought to 25. The African experience of adopting these laws is fairly recent, as the continent ‘lagged behind’ the global norm for a while. Notably, 20 of the 25 African ATI laws were passed just in the last decade.

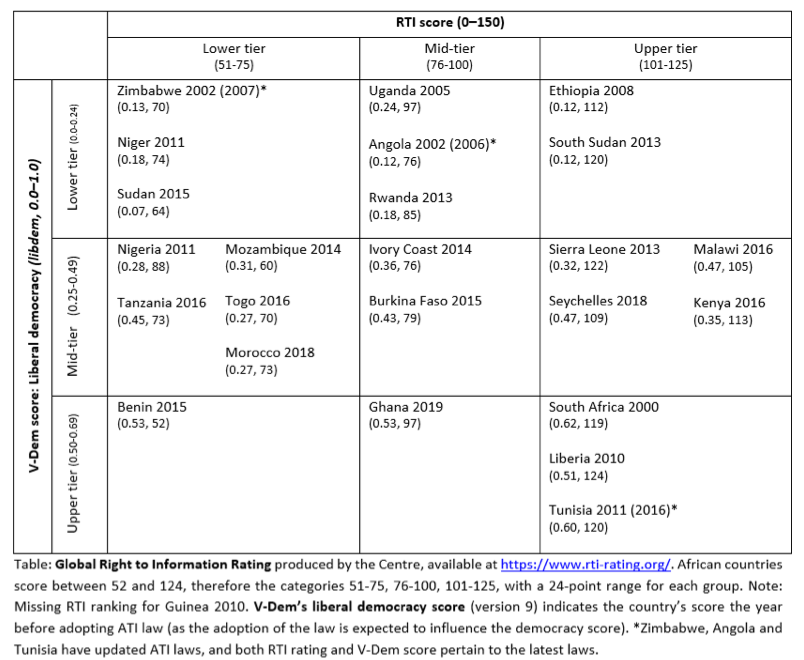

Still, while the global trend shows that legal frameworks to ensure ATI becomes increasingly stronger, there is great variation in these laws across the African continent. Indeed, the drafting of these laws seem to be a ‘double-edged’ sword, where the political process could either result in a strong law, like the highly saluted South African PAIA (2000), or as a government tool to curtail press freedom, like the Zimbabwean AIPPA (2002), considered the most egregious ATI law in Africa.

The African experience so far shows, as illustrated below, that countries with relatively democratic regimes adopt relatively strong ATI laws, and vice versa. However, the variation in quality of ATI laws is greatest amongst the most authoritarian regimes. Some scholars even argue that Zimbabwe’s law should not count as an ATI law at all. The ‘double-edged sword’ thesis seems most applicable to the mid-tier ranging African regimes, however, where most of the resulting laws are either relatively strong or relatively weak.

The two-front advocacy

The recent ‘flurry’ of laws in Africa has to a large extent been assigned to the successful campaigning of so-called ‘right to access activists’ within African states. Globally, the adoption of ATI laws is generally seen as the result of civil society advocacy and ‘push’ for these laws. Governments and political elites, on their side, are seen to be unwilling and resisting, by arguing that ATI laws are merely for the benefit of journalists, certain civil society organisations, and political opponents. By sceptics, ATI laws are framed as just another tool for the country’s already privileged elite.

From my fieldwork interviews with the civil society ‘Right to Information’ coalition in Ghana, one very conscious strategy they employ is exactly to counter this elitist perception of the law. Their aim was to bring it closer to the ordinary citizens and their everyday life, by linking the RTI bill to political promises, embezzlement of public funds, and construction of roads, hospitals, and schools. In order to achieve success, the coalition members argue, it is necessary to make the demand for a Ghanaian ATI law into ‘a people’s demand’. The campaigning for the RTI bill in Ghana was therefore directed both towards politicians and the general public.

In effect, is it all about supply and demand?

Having a nice law on paper says very little about citizen’s actual access to government information, and further, the effects on enhancing people’s everyday lives and their accountability relations with the state. Effective implementation of access to information regimes is key. These laws will not surmount to anything unless there are politicians willing to enforce them at all levels of bureaucracy and citizens ready to make use of them.

As Ghana now embarks on implementing the RTI law, numerous challenges lie ahead. As laid out in a policy brief written with a colleague at Ghana Center on Democratic Development, there are both legal and practical challenges in implementation that could possibly impede citizen’s actual access to information. However, Africa’s fairly recent experience with ATI laws also offers some lessons learned and guidelines on ‘best practices’, ranging from good record-keeping to training of government workers at all levels (see Amanfo and Selvik, 2019).

However, the most powerful mechanism for effective implementation lies in the roam of public engagement. As one RTI coalition member stated at a public forum in Accra this week: “The process of attaining an effective ATI regime is really all about supply and demand”; now that governments have promised to supply, citizens must use the law and demand information.

This blog is written by Lisa-Marie Måseidvåg Selvik, first published on Saktuelt.

References:

Amanfo and Selvik. (2019). “‘Best practices’ in Access to Information implementation – where do we go from here?”. Policy Brief series, Ghana Center on Democratic Development. Accra, Ghana. (Forthcoming.)